Mr. Peanut Summit (Conversation)

Anna Banana, Vincent Trasov, Michael Morris, and Zanna Gilbert

In October 2016, the artists Anna Banana, Michael Morris, and Vincent Trasov came together at the Or Gallery, Vancouver, for the Mr. Peanut Summit, moderated by Zanna Gilbert and hosted by Jeff Khonsary. Their conversation traced the contours of Trasov’s Mr. Peanut project, with the aim of putting the anthropomorphic character’s run for mayor in 1974 in the context of both Vancouver and the international media and mail art scenes.

Zanna Gilbert – It is a great pleasure to be in the room with Mr. Peanut (Vincent Trasov), Marcel Dot (Michael Morris), and Anna Banana. It’s quite a task to introduce the three incredible artists gathered here today. Their practices range from performance, events, publishing, and networking to collecting, archiving, painting, and drawing, including Vincent’s work presented here as part of his new book Mr. Peanut Drawings published by New Documents. When it comes to introducing them to you all, we should take into account that they have been playing around with their own identities. Many of the artists involved in artists’ networks utilize fictional biographies, pseudonyms, and authorship. Each of the invented characters can be considered nodes in that network. Sorry, I don’t mean to call you nodes but...[laughs]. With this freedom to roam, networkers were able to forge new identities by playfully engaging with contemporaries across distances, building up their myths whilst at the same time tearing down those tired old ones usually constructed around artists—those of artistic genius and individual authorship. We’re here to celebrate and discuss Mr. Peanut and to put Vincent Trasov’s performative legacy into context, both here in Vancouver and internationally, with the help of Anna Banana and Michael Morris. We might have here three of Canada’s most important artists so no doubt it’s going to be special and memorable evening. Vincent Trasov is from Edmonton, Alberta. In the late 1960s he began experimenting with process and conceptual compositions, including painting and performances, investigating the properties of fire and its effects on different materials. He also began working with video during this time. In 1969, together with Michael Morris, Trasov founded the now legendary Image Bank, a system of postal correspondence between artists that facilitated the exchange of information and ideas. In 1973, again alongside Morris and several others, Trasov co-founded the Western Front. In 1970, he assumed the identity of Mr. Peanut to investigate issues of contemporary performance. By 1974, fellow artist John Mitchell proposed that Mr. Peanut run for the office of mayor of Vancouver. In 1999, Trasov was selected by the Vancouver Sun as part of the top one hundred British Columbians who’ve shaped the province over the past century. He currently lives in Vancouver and in Brandenstein, Germany. In 2000, he returned to the alter ego of Mr. Peanut and began a series of drawings that explore the character in various settings, from everyday occupations to iconic monuments and touristic spots. Michael Morris is a painter, photographer, video and performance artist, and curator. Like Trasov, his work has often been media based and involved with developing networks and in the production and presentation of new art activity. He was born in England and moved to Canada when he was four, returning to the UK for his graduate study at the Slade School of Fine Art in the mid 1960s, where he became acquainted with concrete poetry at the Destruction in Art symposium, led by Gustav Metzger at the Institute of Contemporary Arts (ICA). His own drawings were included in the exhibition of concrete poetry that he organized at the University of British Columbia (UBC). With Trasov, along with the aforementioned achievements of both the Image Bank and the Western Front, and artist residencies at Berliner Künstlerprogramm des DAAD in Berlin and the Banff Centre, he founded the Morris/Trasov Archive, now housed at the Morris and Helen Belkin Art Gallery in Vancouver. Anna Banana is known for her performance art, her writing, mail art and artist stamps, and as a small press publisher. In an early act of performance, she declared herself the Town Fool of Victoria. She’s been prominent in the mail art movement since the early 1970s. As a publisher she launched VILE magazine, which published between 1974 and ’80, and the Banana Rag newsletter — the latter became Artistamp News in 1991. In 1973, she moved to San Francisco to join artists she met through the network known as the Bay Area Dadaists. Anna lives in British Columbia and operates Banana Productions, which prints the International Art Post.

Jeff Khonsary – Welcome, everyone! We are going to watch a few video pieces. The first is a film of the Banana Olympics held in San Francisco in 1975 — “the international banana event,” as the film declares—followed by television coverage of the Mr. Peanut Campaign for Mayor.

(...)

Zanna – I think it would be interesting to think about how both of those videos we just saw are extremely joyous, in contrast to the usual kind of discourses that happen in the public sphere. I’m sure the issue of seriousness gets raised around this work all the time. How do you respond to people asking you “Are you serious? Can this be art”? Perhaps we’ll start with Anna.

Anna Banana – Well certainly, I’m serious about doing things that engage people. That’s what my work is really about — setting up parameters that make it possible for people to interact [with the situation I’m creating].

Vincent Trasov – We treated the city as a stage, an art city. We built costumes. It was a large-scale process. I was most concerned with the technical problems: How do you frame an image within the city? How — like Anna says — do you involve the public? We weren’t just doing things in the Grand Luxe at Western Front. We were going out onto the streets and treating it like a stage and involving the passers-by. We were taking pictures. Anna was with us on occasions, Dr. Brute — different people and artists forming a troupe and getting along.

Michael Morris – I think part of the philosophy of that specific time was influenced by people in the Fluxus group and others, who we’d been involved with. [It was this idea] that art and life are one and the same. That’s part of the moment of this particular time. When I came back from doing my postgraduate work in London, I was quite excited about being back in the West [Coast], and in Vancouver. You think about Gertrude Stein being interviewed in Oakland after she came back to America in the late ’30s — and she said the problem with Oakland is that there was no there, there. In a sense, things were similar with Vancouver at the time. My roots with the Vancouver scene really began with Malcolm Lowry and [his 1947 novel] Under the Volcano, when Vancouver is being talked about for the first time, and being written about. And the group of people that came around in Dollarton and the Mud Flats [in North Vancouver] — people like Al Neil and that. And when I went to art school, all the people that were left were from that group, drank beer around the corner in the Alcazar Hotel [in Vancouver] and I would sit there for 35¢ beers and listen to their stories.

Zanna – Vincent, can you talk about the genesis of Mr. Peanut and your early performances—how it all happened? Because the mayoral campaign came after many years of engagement with this persona.

Vincent – When I started as an artist, I didn’t have an identity or an ego to worry about—it’s kind of changed a bit over the years but [laughs]. When I decided to become an artist, I slipped into a kind of metamorphosis. Mr. Peanut was a childhood figure: I had a colouring book from when I toured Planters’ factory. I started animating Mr. Peanut tap dancing at Intermedia [now VIVO Media Arts Centre, Vancouver] in 1969, with the idea of completing a 16 mm film. But it got too much to do all these drawings, so I thought maybe it would be easier to make a costume, and then I could animate me dancing, and that’s how that started. I was interested in anthropomorphics. Getting into the costume shell allowed me to assume a new identity. I had all these different avenues I began exploring as Mr. Peanut...

Michael – I met Vincent through Intermedia. And he was interested in animation and cinema—we all were—and there was a little bit of equipment there. There was a spirit of collaboration — and I think that is where Mr. Peanut comes in: he was willing to be around everybody and to contribute to what they were doing. Intermedia was a very important part of what happened later in the ’70s, leading to performance at the Western Front.

Zanna – Michael, can you talk a little bit about your experiences in London? You found yourself in the middle of an early concrete poetry scene and the Destruction in Art symposium that was run by Gustav Metzger, as I mentioned. How do you feel that impacted you as an artist? And what you brought with you when you got back to Vancouver?

Michael – Sort of in a nutshell...[laughs] It was a wonderful experience being in London in the mid ’60s. I was twenty-three years old. I’d studied at the Vancouver School of Art with Jack Shadbolt and Roy Kiyooka. I had a sense of West Coast modernism and all of that, had grown up with that. In London, youth culture had just exploded, and I was part of it, and we were impatient. We wanted to address the world and we were looking for new ways of seeing things. I became disillusioned with the Slade School. I thought it was such a... not really interesting place. At that time, I was attracted to what was happening at the ICA, and the program that they had there. There were people from all over the world at the ICA, from not just England. And I was going to Paris and I ran into some, you know, young Americans who worked for [the art dealer] Ileana Sonnabend. I would go there and help them put the addresses on invitations for openings, and that was funny: “Oh my goodness, there’s so and so’s address. Oh my god, that’s Man Ray’s address.” And I would keep note of these things, while I was writing the invitations. When I came back to Vancouver, I thought: “Oh my god, if I had 500 bucks in my pocket, I would go back directly [to London].” But I didn’t, and you realize that, you know, there was a lot of work to be done [here in Vancouver]. This was right after the Canadian centennial [in 1967]. For the first time, there was a new recognition of younger artists in the West. It was an important moment—you could feel like you could address the country and the world.

Zanna – Vincent, I wanted to ask you whether you thought there was context for your early performance work — the paintings that you made that experimented with fire, for example. Did you feel like you had structure with which to do this work? Did UBC provide you a forum for the performance pieces you made before you embarked on Mr. Peanut?

Vincent – Yes, exactly. Alvin Balkind from the UBC Fine Arts Gallery always supported my work — all of our work, really. He had a little gallery in the basement of the Fine Arts Gallery. Michael organized the Concrete Poetry show there back in 1969. We invited Ray Johnson to come and show his collages there — he was just starting the New York Correspondence School. We also did a postcard show there back in 1971 to celebrate the hundredth anniversary of the picture postcard.

Michael – When Alvin Balkind left the New Design Gallery to work at UBC Fine Arts Gallery, he immediately brought in people like Helen Goodwin, the choreographer and dancer. People in the arts in the university started an avant-garde festival in the early ’60s, and that’s when I was going to art school and we went there. All of the artists at the time [in Vancouver] looked at UBC as an important part of where we would meet people and discuss ideas. Thank god for Alvin.

Zanna – Anna, around this time, you stopped making objects and began focusing on events—becoming the Town Fool of Victoria. Can you tell us about this decision? And also what kind of events you organized?

Anna – [In Victoria,] I didn’t have the support system like these guys did at UBC. I had been a teacher at the New School in Vancouver, became overwhelmed, and left to spend a couple of years at the Esalen Institute in Big Sur. When I came back, I was uprooted really, and ended up living in Sooke, BC, in a little beach cabin. I was very isolated, trying to figure out how to connect with the community there, what I could do to be creative and make some impression. And the Town Fool — well, it evolved.... When I was living in Sooke, I was on a beach that created these incredible symmetrical stones, and I started painting geometric designs on them and I thought, “Let’s see, Bastion Square...that’s the place where all the tourists arrive [in Sooke]. Maybe if I put a bunch of stones on this table [in the square], people will look at them and I can start a conversation and make connections.” But I thought, “Well that’s kind of boring—selling stuff. What else could I do?” The Town Fool emerged out of all this. I decided I could put a petition out against nuclear testing. My banana identity started at the New School — the kids at the school started calling me Annie Banani, because my name originally was Anne. At Esalen, the name returned: when I was the breakfast and lunch cook there, they started calling me Anna Banana after I accidentally fell in a box of bananas on a mountain in Big Sur. At Bastion Square, I started asking people for their “banana stories” — which, believe it or not, just about everyone has.

Zanna – I have had moments when I wondered if the banana was this kind of...appendage that would allow you to be a male artist. Because mail art is dominated by male artists...

Anna – I hadn’t really played around with that...

Zanna – There’s still time. [laughs] The subtext of Image Bank is the way an image can function as an empty signifier — and, like the banana, it becomes this way of connecting. I think Mr. Peanut works in that way as well. With Image Bank, you were trying to create an alternative image economy. Could you tell us about the founding of Image Bank?

Anna – Michael, was there a germinal image that started it?

Michael – There’s numerous things that made Image Bank possible. I think, largely, it was the experience of organizing the Concrete Poetry show and the excitement of people sending work for an exhibition from all over the world, and the excitement of those pieces arriving, and the correspondence that goes back and forth with that. And you know at this time, it was 1969 in Vancouver, people couldn’t imagine how to address something to the world, internationally. In those days, nothing went over the Rockies—in either direction. And everything that happened in Canada was really parochial. Canada only addressed itself. People were quite proud of this “Maritime art” and this, that, and the other. We wanted to forget about being from this, that, or the other. We wanted to address the world. I was going down to Los Angeles and meeting people there. In those days, we knew everyone up and down the coast, from San Diego to Vancouver. We knew the whole scene in those days. And that went on to the Western Front, with all of its activity. And I guess Intermedia also had a part in this.

Anna – I was wondering when you were going to bring them in.

Vincent – What about the postal system?

Michael – We invited Ray Johnson — and I remember he was using the post for his New York Correspondence School. He was organizing an exhibition at the Whitney, of all of that.

Zanna – Who set up the Corres Sponge Dance School?

Vincent – Glenn Lewis.

Michael – [The Corres Sponge Dance School] came out of our involvement with a wider community. There were zillions of networks — everyone had theirs. Everyone wanted to have their own network, and they did!

Anna – Can I tell a story about you?

Michael – Yes of course. [laughs]

Anna – At one point I asked Michael how he connected with Ray Johnson. What Michael told me was that one of Michael’s Nothing paintings was in Art in America and Ray Johnson saw that issue and he got in touch by sending a letter to Michael care of the Vancouver Art Gallery. The letter said: “To Michael, I am also doing Nothings.” This is when Ray Johnson would go to some art gathering event and he would announce it as an event, but he would do nothing.

Michael – I got this letter, I had no idea who [Johnson] was, but it was curious and I sent something back to him. And I got something more, and then the letters started coming. And then I was organizing the Concrete Poetry show, and I thought — why not invite Correspondence?

Anna – And I think he came, didn’t he?

Michael – He did, he came for it.

Zanna – Ray Johnson started doing Nothings because everyone else was doing Happenings.... I’m also interested to know about the technical way Image Bank actually worked. How did you begin? I know you had address lists, but how did it proliferate so widely? Because you really became known internationally. What was the aim of Image Bank? Were you distributing images, or were you trying to make contacts with like-minded people, or...?

Michael – Yes, more like that. And just having a sense of fun and a bit of nonsense with this. We always enjoyed collages, and Ray Johnson was part of that. And we always loved correspondence. We wanted to do something new, something different. We created a network, and 1971 was, it turned out, the hundredth anniversary of the picture postcard. So we asked Alvin Balkind if we could organize a postcard show where we’d invite all the people that we’d made contacts with to send postcards and we would publish a postcard edition. And it was fabulous — it’s a wonderful collection, a very important body of original collage pieces, photos, whatever, from all kinds of important people [laughs] from all over.

Zanna – Gordon Matta-Clark, Vito Acconci, Eleanor Antin, Robert Filliou...

Michael – Yvonne Rainer, and Anna Banana...

Zanna – Anna, can you tell us how receiving the Image Bank list of addresses affected you? Because I’ve read some stories about this where... Perhaps it bears explaining — the Image Bank request list had addresses of artists requesting images of certain types.

Anna – [The list] was wonderful. It felt like I’d died and gone to heaven, because, you know, Victoria — if you think Vancouver is stale, try Victoria. People thought I was crazy! Literally, they thought I was crazy! It was pretty hard. And here comes this list, with all these people, and they wanted skies, or lips, or ’50s cars, or whatever it was. And I went, “Wow, this looks interesting.” And I sat down, and I collected old magazines and so on, and I spent all kind of time clipping the images that each person wanted, and I put that together with a copy of my first or second or third issue of the Banana Rag and I said, “I want anything and everything about bananas—images or stories, I don’t care.” And my mailbox lit up, and so did I. It ended my feeling of isolation.

Vincent – This is how we got to know people. First of all we would correspond with them, and then if it got more and more personal, and we really had to meet each other, we would go, travel down the coast to different centres and meet artists — that’s how it kind of happened.

Michael – There were these ideas of being independent from the Canada Council and other funders. So eight of us founded a group together and looked for a place we could do what we wanted to do, to create this kind of thing. That’s how the Western Front came about, out of all of that activity. And we started to invite people and by 1974 we did an issue of FILE magazine. It was a huge amount of work to put it all together. We did this with Kate Craig and everyone else at the Western Front. It had a beautiful cover by Robert Cumming of Ben Vautier. But we really couldn’t handle it anymore, we were involved with the Western Front, we were bringing people there... * *

Anna – There was another connection — with General Idea, the artists in Toronto who put FILE magazine out. You collected all of the information, the address lists, but they actually got it published. FILE was very influential to me — it was through FILE magazine that I started VILE. There were complaint letters in FILE magazine about the “quick copy crap” they were receiving. This was from some of the artists from San Francisco — I was in San Francisco — and I was like, “Well I happen to think that this is really a wonderful thing,” and I wanted to respond in kind. I was thriving through the mail art I was receiving—I thought it was fabulous. It wasn’t all great art, I acknowledge that, but it was the concept of the connection of that network. And it started with these guys [points to Michael and Vincent], and FILE.

Michael – Shortly after that issue of FILE magazine, LIFE magazine sued them. It was a sign of the visibility of that project. After we published the Image Bank postcards, we found out that somebody had started an image service [company] called Image Bank and had copyrighted the name. The phrase [originally] came from William S. Burroughs and Claude Lévi-Strauss. We’d written letters to Lévi-Strauss and Burroughs and had letters from them encouraging us to use the term. We had used the name with permission and had just gone along da-da-da-da until all of a sudden we wanted to distribute our postcards in New York and couldn’t.

Vincent – That’s when it became the Morris/Trasov Archive.

Michael – That’s when it became the Morris/Trasov Archive, and everything else came from that.

Vincent – And then we got into the idea of the archive.

Zanna – And here we are.

Michael – The open-endedness of the banana and the Image Bank was that we never...everybody became a banker. They deposited an image and they took out an account, became an image banker. So it was very altruistic.

Zanna – But it was a currency.

Vincent – It was.

Anna – I never got an account number. [laughs]

Zanna – Every artist that gets involved in a network such as this ends up with a huge collection — it forces you to be an archivist, really. There’s the one model where you work with an institution and they take over that. But then there are certain kinds of compromises because of that. The institution’s logic sort of imposes itself on the collection. And then there’s the other entropy method, where you just kind of hold onto it, and kind of do nothing.

Anna – Where do you think all the content for the Banana Rag came from, for heaven’s sake? People would send me newspapers, magazine articles, pictures, and drawings, and so on and I turned it into a newsletter, and continue to collect material. And the culmination of all that...

Zanna – You’re constantly processing it...

Anna – I’m processing it, the whole collection, but you know we had touched on this earlier. I have started the work of cataloguing my collections. I have six whole archive boxes of stamps, artists’ stamps, that were created by the artists in the network. So I have in some ways sorted some of it already, begun the process of organizing the material. But I’m interested in going through, of being able to write about what it meant to me, how people were so generous. I don’t know if any of you know about my show in Victoria...

Vincent – ...Last year.

Anna – I gave away about 1,200 banana items that people had sent to me. They were all in a catalogue made by the people at Open Space. The women who catalogued them said she became very possessive of the collection and she was jealous when people would start picking. The conditions were, as with most of my work, that they had to catalogue that item, they had to measure it, weigh it, draw it, and tell me what material it was. So they couldn’t just walk out of the gallery with the item — they had to complete these catalogue forms.

Zanna* – Oh that’s very smart.

Audience – I was wondering if you could tell us a little bit more about John Mitchell’s practice. I know that he was very important to the mayoral campaign. Was that project kind of indicative of what he was doing at the time? How did that unfold?

Michael – It originally came out of an early group named PUMPS — a wonderful bunch of younger artists. They would come to our events at the Western Front and we would go to their events at PUMPS [Centre for the Arts], and we would often collaborate on projects and things like that. Out of this relationship, John Mitchell and Vincent became good friends. They were both sculptors, or interested in sculpture — John coded himself as a sculptor. He was interested in Vincent as a performing sculpture. The possibilities of going into the mayoralty campaign came out of that relationship through a group of artists at the Western Front and PUMPS. The campaign really made us visible within the city. That’s what John was trying to do — to address the role of the artist within the city. John’s really an important person in all that.

Vincent – It was very sad, John’s passing [in 1991]. He hasn’t been recognized. He was an artist with many ideas and there needs to be a whole new body of research. People are trying to find out where John’s work is. [The artist] Neil Campbell has several of the notebooks. In my feeling, [John’s] notebooks and diaries are his most important works.

Audience – I know about the Morris/Trasov Archive at [UBC], but I wanted to hear from all of you about when it became important to start saving or systematically organizing your accumulations. When did you feel ready to tell your stories?

Michael – We always thought it was very important, right from the beginning.

Audience – Was there a moment when it became more systematic?

Vincent – When Michael and I were in Berlin, we’d left all our Image Bank accumulation in cardboard boxes in the basement of Western Front. We knew that it was foxing and moulding and that it was time to address it. In 1991, we had a chance to take it all to the Banff Centre, through [the curator] Lorne Falk, who was there at the time.

Michael – That’s when we created the archive.

Vincent – That’s when we accessioned every item in the archive.

Michael – By the end of the ’70s, both Vincent and I had basically done everything we wanted to do with people at the Western Front. It was time to move on and for another generation to come in. We were very lucky to be invited to the artist residency program at DAAD, and we jumped.

Zanna – In Berlin?

Michael – Yes. In 1981. When Vincent and I were invited to Berlin, we were exotic. They really hadn’t had Canadians there.

Zanna – Westerners no less...

Michael – And as you know now, half of Vancouver is in Berlin. And I think that really comes a little bit out of our networking that we did way back then.

Vincent – What about Anna’s archive?

Anna – Well, I kept everything and filed it, categorically, alphabetically. It’s in boxes and I’m in the processes now of attempting to do an inventory of it, looking for a home for it. Because, as you all know, we’re not going on forever. I had several tours through Europe where my mail art correspondents hosted me in their homes and set up dates for me to do various performances and events, starting in I think it was, ’80 — no it must have been in the ’70s...

Michael – We saw you in Europe from time to time.

Anna – That’s right. I did a tour with the mail artist [Bill] Gaglione, touring Italian futurist theatres. We went to twenty-nine different cities in three and a half months. Having never travelled very far—it was just gruelling. Since then, I’ve also done several solo tours. My correspondences spawned a great deal of activity. The material has been filed, and now what I really want to do is somehow make it into a form that could be put together and published. But in order to do that, I have to go through the material and inventory it. I’ve started cataloguing, but I’ve been thinking, “Oof, this is going to take me the rest of my life.”

Audience – I have a question about the [form of a] magazine within this context. You mentioned that Ray Johnson had gotten in touch with you because your Nothing painting was reproduced in a magazine. It feels like magazines were tremendously important internationally at the time.

Michael – Anna, could you talk more about VILE magazine?

Anna – Like I said earlier, VILE was a response to the criticism of FILE magazine, from people that were published in FILE magazine. I self-published [VILE]. I think I did get an award from the Coordinating Council of Literary Magazines when I was living in San Francisco — that was how one of the issues was funded. But basically [the magazine] was my art. Like artists who buy paint and canvas and other materials — I was a publisher. It’s a way of putting material [from my archives] into the world, rather than simply having it in file cabinets in my home.

Vincent – Publish or perish.

Anna – Exactly.

Notes

This Supplement is produced in collaboration with the Morris and Helen Belkin Art Gallery at the University of British Columbia, Vancouver.

Read Supplement 5’s Introduction by Zanna Gilbert here.

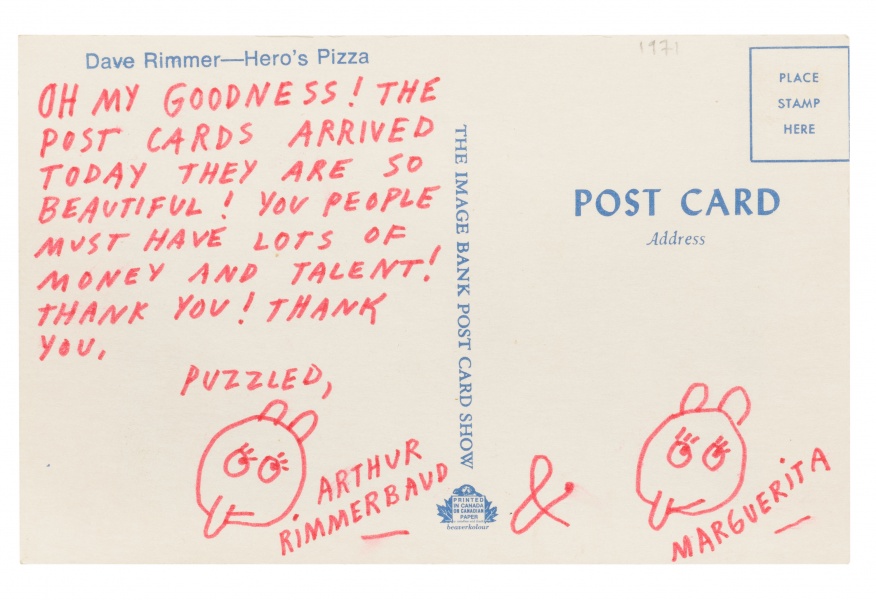

Image: Ray Johnson, postcard, c. 1971. Collection of the Morris and Helen Belkin Art Gallery, Morris/Trasov Archive. Courtesy of the Ray Johnson Estate.

About the Authors

Anna Banana is a Robert’s Creek–based conceptual, performance, and mail artist. In 1971, she founded the Banana Rag, a newsletter that connected her with the International Mail Art Network (IMAN). In 1973, she founded VILE magazine in San Francisco, a publication that was a parody of both LIFE magazine and General Idea’s FILE Megazine and that documented the work of international mail artists. A retrospective of her work, Anna Banana: 45 Years of Fooling Around with A. Banana, was recently organized at the Art Gallery of Greater Victoria.

Vincent Trasov is a Vancouver- and Berlin-based painter, video, and performance artist. He is a co-founder of the Western Front Society. With Vincent Trasov he founded Image Bank in 1969, a method for personal exchange between artists, and the Morris/Trasov Archive in 1990, currently housed at the Morris and Helen Belkin Art Gallery, Vancouver. In the early 1970s, Trasov assumed the role of Mr. Peanut, eventually running for Mayor of Vancouver in 1974 with the assistance of fellow artists Michael Morris and John Mitchell.

Michael Morris is Vancouver-based painter, photographer, video and performance artist, and curator. His work is often media based and collaborative, and his practice is involved with developing networks and the production and presentation of new art activity. He is a co-founder of the Western Front Society. With Vincent Trasov he founded Image Bank in 1969, a method for personal exchange between artists, and the Morris/Trasov Archive in 1990, currently housed at the Morris and Helen Belkin Art Gallery, Vancouver.

Zanna Gilbert is a postdoctoral fellow at the Museum of Modern Art, New York, and is co-editor of post.at.moma.org. She completed her PhD with Tate and the University of Essex in 2012 and curated the exhibitions Felipe Ehrenberg: Works from the Tate Archive (2009); Intimate Bureaucracies: Art and the Mail (2011); Contested Games: Mexico 68’s Design Revolution (2012); a retrospective of the Brazilian artist Daniel Santiago with Cristiana Tejo (2012, 2014); It Narratives: The Movement of Art as Information with Brian Droitcour (Franklin Street Works, Stamford, 2014); Edgardo Antonio Vigo: The Unmaker of Objects with Jenny Tobias (MoMA, New York, 2014); and Home Archives with David Horvitz (Chert Berlin, 2015).