Mr. Peanut Summit (Introduction)

Zanna Gilbert

Like many of the artists that formed the international mail art network, Canadian artists Anna Banana, Michael Morris, and Vincent Trasov played with the personal effacement afforded by the anonymity of communicating at a distance. A number of these artists employed fictional biographies and pseudonyms or subverted traditional hallmarks of authorship such as the signature, ditching the individually created work in favour of a Ray Johnson-inflected “add to and return” aesthetic that embraced collaboratively created works. Indeed, the collaborative nature of networking created a web of activity made up of thousands of individually authored or co-authored threads.

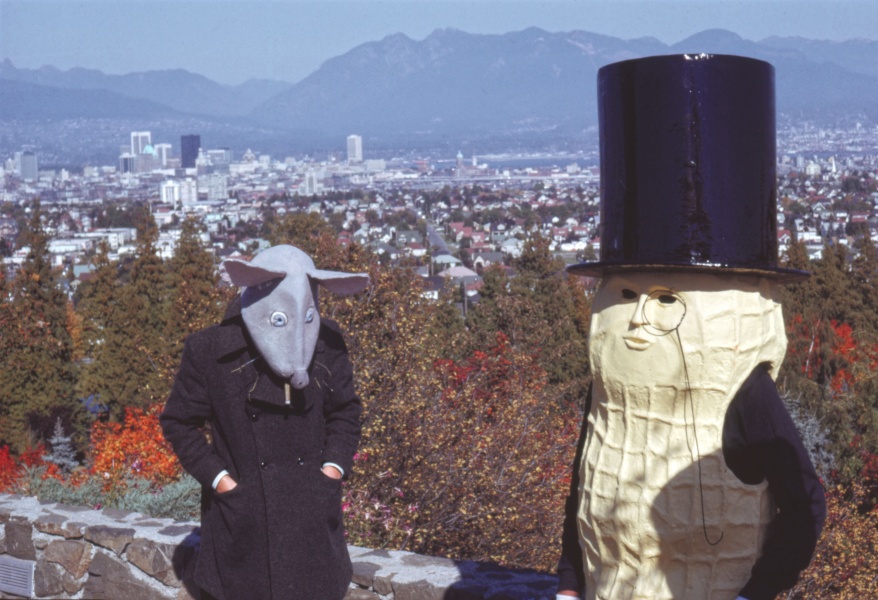

For the Mr. Peanut Summit at the Or Gallery, Vancouver in 2016, Trasov and Morris brought along their alter egos: Mr. Peanut and Marcel Dot. Fellow Summit participant Anna Banana had no choice but to invite hers, since she had already officially and fully embraced her adopted moniker in 1972 with a legal name change. Historically, these artists used costuming as part of performative actions, such as Mr. Peanut’s 1974 Vancouver mayoral campaign or Anna Banana’s Town Fool (1970–71) and Banana Olympics (1975/80). Each of these artists’ characters could also be considered a node in a network in which outlandish identities were circulated and relayed. The inhabited identities were often larger than life, entailing playfully absurdist performances that take place both locally and at a distance, proliferating through the network as icons. Through this process, artists rebuilt the myths usually constructed around artists—namely, the concepts of artistic genius and individual authorship—and queered the conservative heteronormativity of the era.

An initial fortuitous mail encounter between Vancouver and New York was premised on another form of printed communication: the art magazine. Michael Morris was an abstract painter who had interrogated the philosophical “problem of nothing” in comic-strip, pop-op style. On seeing this work reproduced in Artforum in 1967, Ray Johnson—founder of the New York Correspondence School—wrote to Morris over their joint appreciation of “nothing.” Morris’s 1969 series of huge Letter paintings foretold the importance the post would take on in his work, connecting art to the act of communication itself, something that would later come to define Morris’s activities at Vancouver’s Western Front (founded in 1972 by Morris and Trasov alongside artists Martin Bertlett, Mo van Nostrand, Kate Craig, Henry Greenhow, Gary Lee-Nova, Glenn Lewis, and Eric Metcalfe) and Image Bank (founded in 1970 by Morris, Trasov, and Gary Lee-Nova). The paintings refer to the “Letter” column in Art International magazine and broach the gulf between abstract art and the 1960s turn to media and communication. Curator David MacWilliam notes a common factor in Morris’s abstract paintings and his later activities: that of the virtual image or cipher, with “allusive references to archetypal images.”1 MacWilliam detects colours derived from the mediated language of graphic design: “Green was the felt green of a pool table; blue was from a cigarette package.... Morris would choose colours for his paintings from a candy wrapper or a perfume advertisement.” Through his leading role in the establishment of both Image Bank and The Western Front, Morris was able to continue his research into what MacWilliam calls “the mythographic,” a mode of artistic exchange of imagery that drew upon the post-war experience of industrialized image making and, as MacWilliam puts it, “its massification via spectacle.”2

Mr. Peanut, the mascot of the Planters food corporation, was appropriated by Vincent Trasov first as a childhood obsession and then, in the 1970s, as a full-blown alter ego. Trasov took this grotesque-debonair brand logo, first introduced as the face of Planters in 1918, and thrust it into live performance, most notably in the Mr. Peanut mayoralty campaign in 1974. As the art critic Nancy Tousley has noted, Trasov’s Mr. Peanut embodied a parodic monumentality, conceived as an incursion into everyday life in the city of Vancouver through the city’s networks of media and politics.3 Mr. Peanut campaigned under the slogan “A New Era. A New Mayor. An Art City,” a campaign that invoked the most avant-garde of principles: the attempt to unite art and life. Artists proposed to convert the city into a stage for artistic actions. By creating “social sculptures”—to use Joseph Beuys’s term—Mr. Peanut and his comrades brought performance art into the urban environment. Notably, artist John Mitchell, instigator and spokesperson of the mayoral campaign, was deeply committed to the seriousness and social good of communicating artistic values to society at large.

In the early 1970s, Anna Banana found her marriage to be stifling and felt a need to connect with other like-minded people. This basic desire for communication and communion also became the guiding principle of her work: interactivity. Banana is a performance artist and avid networker, weaving a twin performativity through both her bodily presence in gatherings in public space and via the mail art network, through which she circulated her publications and news of her performances. Like other women artists of her generation, she paid a dear price for her decision to become an artist, losing contact with her family as a result. Her early decision to create something—anything—to serve as the basis for communication became a modus operandi, and she chose the simple and ubiquitous motif of the banana. Like Mr. Peanut, the cipher, Anna Banana’s “bananology” was the empty signifier—a sustaining centre, perhaps even a conversation starter, to which anyone could respond. With Banana’s uncompromising and avid energy, the motif was able to sustain a wide range of activities, lending coherence to her mail art, performance, and publishing activities. It functioned almost as an uncanny, tongue-in-cheek brand through which she would come to organize the Banana Olympics events in San Francisco in 1975 and at Bear Creek Park, British Columbia, in 1980. The public masquerade and joy of these events upended the sometimes austere and serious tone of artists’ public activities, and they draw obvious comparisons with Mr. Peanut’s intervention in public space.

As publisher, Anna Banana worked for years on a variety of enterprises, the first of which was the Banana Rag (1971–91/1996–2016); eight editions of VILE (1975–80), created to counter FILE Megazine’s claim in the 1970s that mail art was dead; Aristamp News (1991–96); and Artiststamps (1991), which documents the history of both Artist Stamp News and works by other mail art artists. When distributing early versions of these magazines in Vancouver in 1971, she met Gary Lee-Nova—who took on the pseudonym Art Rat in the 1970s—and was thereby introduced to Morris and Trasov’s Image Bank, through which she established hundreds of correspondents.4

The Vancouver of the 1960s was “aggressively cosmopolitan...unrivalled in its energy, vitality, and feeling of the times,” as characterized by MacWilliams. Yet Morris also remembers its parochial and conservative tenor, and when he moved to London, England, for a scholarship at the Slade School of Art in 1965, he took a deep breath of the city’s cosmopolitanism, bringing that spirit back with him when he returned to Vancouver. This group of artists found ways to destabilize the conservative and heteronormative expectations of society by exploring the dichotomies of high/low and nature/culture—revealing how these opposites were present in images that circulated through media networks. Mr. Peanut himself represents a curiously queer example: as primitive foodstuff and a media icon, the dandy, degendered nut was able to provoke anthropological questions about nature and culture in a way that ultimately subverted masculine identification. The “Mr.” in “Mr. Peanut” is undercut by the sexless, campy, tap-dancing, vaudevillian character who is both nude and dressed at the same time. In photographs of Trasov as Mr. Peanut posed outside with General Idea attaché Granada Gazelle (Granada Venne), an eerie heteronormativity is performed though an affected, absurd “romance.” Reappearing under the title Children of Hollywood in the 1977 Image Bank Postcard Show, these photographs only further queer the corporate mascot, feigning a sexuality whose absurdity is ultimately turned back on itself.

The kitsch of mainstream media culture was explored to extreme lengths by other artists in Vancouver in the 1970s, including by Dr. Brute and Lady Brute (Eric Metcalfe and Kate Craig), who dressed in leopard print and tried to shake off social mores. Anna Banana’s own experiences of conservative and normative expectations, stultifying for a woman artist at the time, led her to seek out experiences in art, performance, and sociability. In some ways, then, the performative roles taken on by this group of artists were a symptom of a period marked by patriarchal normativity.

The site of these explorations was Vancouver, a tightly knit West Coast metropolis. Its position on the periphery led to a complex history of engagement with various major art centres—interactions expedited by the history of an increasingly dematerialized art object. What if Gertrude Stein’s famous quip about Oakland, “There is no there there” (also uttered by Morris to describe 1960s Vancouver) was not a pejorative but the recognition of infinite possibility? The city’s geographic remove, at once a blessing and a curse, mobilized many artists to initiate their own institution-building projects, such as pseudo-corporations like Image Bank and the N.E. Thing Co.—another Vancouver based entity that explored corporate aesthetics in networked art—and artist-led projects like the Western Front. Cultural theorist Craig Saper has pointed out how Anna Banana’s “organic mail art networks lampoon the corporate model of market networks.”5 Like Anna Banana’s fruity “brand,” a range of pseudo-institutions with semi-corporate aesthetics arose.

Image Bank was invented by Morris and Trasov as an exchange network—literally a “bank,” with visual material as currency—through which interested parties could trade images. Instead of being based on cold, hard currency, the project was born of a need for “personal, direct contacts and communications among artists in Canada and abroad.”6 Image Bank sent out compiled image-request lists to artists, friends, and publishing directories. Both the Western Front and Image Bank thus engaged in the establishment of broad networks of exchange with artists all around the globe, enabling the circulation of images through kindred affective ties. Morris and Trasov’s joint venture only ever existed “in the mind” and was, by account of the artists, “telepathic.”7 Unlike the N.E. Thing Co., Image Bank was never incorporated. But it explored the possibilities of alternative institution building, just as the Western Front would a few years later. Like their Toronto-based counterpart, General Idea, Image Bank was invested in images and their circulation. These concerns for the image as empty signifier, or repository of dreams, was embodied by the detournement of an icon such as Mr. Peanut and his collaborators. Despite relying on the hardware of the postal system, the spirit of exchange was precocious in its virtuality. An early example of the extent to which images and visuality exert unbounded influences on us, Image Bank called forth a network of cut and paste for the predigital age.

Notes

- David MacWilliam, “The Problem of Nothing,” in Watson, Scott, Letters: Michael Morris and Concrete Poetry, ed. Scott Watson, exhibition catalogue (London: Black Dog, 2015), 25. Originally published in Michael Morris: Early Works 1965–1972, exhibition catalogue (Victoria: Art Gallery of Greater Victoria, 1985).

- MacWilliam, “The Problem of Nothing,” 25.

- Nancy Tousley, “Mr. Peanut Then and Now,” in Mr. Peanut Drawings (Los Angeles: New Documents, 2017), 79–83.

- See Craig Saper, “The Banana Paradox,” in Anna Banana: 45 Years of Fooling Around with A. Banana, ed. Michelle Jacques, exhibition catalogue (Victoria: Art Gallery of Greater Victoria), 65–81.

- Saper, “The Banana Paradox,” 70.

- “History of the Image Bank and the Morris/Trasov Archive.” Vincent Trasov’s website https://fillip.ca/kytl.

- “History of the Image Bank.”

This Supplement is produced in collaboration with the Morris and Helen Belkin Art Gallery at the University of British Columbia, Vancouver.

Read the transcript of the discussion between Anna Banana, Vincent Trasov, Michael Morris and Zanna Gilbert here.

Image:

About the Author

Zanna Gilbert is a postdoctoral fellow at the Museum of Modern Art, New York, and is co-editor of post.at.moma.org. She completed her PhD with Tate and the University of Essex in 2012 and curated the exhibitions Felipe Ehrenberg: Works from the Tate Archive (2009); Intimate Bureaucracies: Art and the Mail (2011); Contested Games: Mexico 68’s Design Revolution (2012); a retrospective of the Brazilian artist Daniel Santiago with Cristiana Tejo (2012, 2014); It Narratives: The Movement of Art as Information with Brian Droitcour (Franklin Street Works, Stamford, 2014); Edgardo Antonio Vigo: The Unmaker of Objects with Jenny Tobias (MoMA, New York, 2014); and Home Archives with David Horvitz (Chert Berlin, 2015).